My Maniac Week - A Review

Table of Contents

Previously: Upcoming Maniac Week.

Summary #

Inspired by Nick Winter, Bethany Soule, Danny Reeves, Brent Yorgey, and Alex Strick, I undertook a “maniac week” from Friday, October 9th (9:00 AM) through Thursday, October 15th (12:00 PM). During my maniac week, I worked 11+ hours a day on schoolwork and my primary research project while avoiding social media and other internet distractions.

By my own assessment, my maniac week was a success. Despite not working nearly as many hours as Nick Winter, I got everything I needed to done, learned that I could work as much as I did, and observed the challenges working a lot entails. Equally important, I enjoyed myself in the process, both in the type 1 and type 2 fun senses.

Work time #

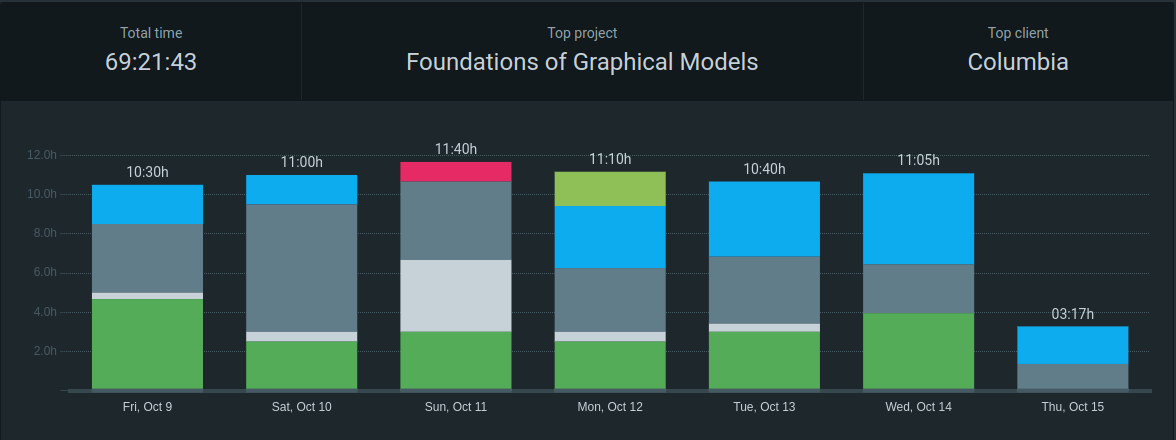

As shown below in my clockify time summary, I averaged 11 (technically 10.993) hours of work per day during my 6 full days of work, with an additional 3.25 hours of work done on the final day, Thursday. This sums to a total of 69:21 hours of work over the course of 6 (plus one third) days.

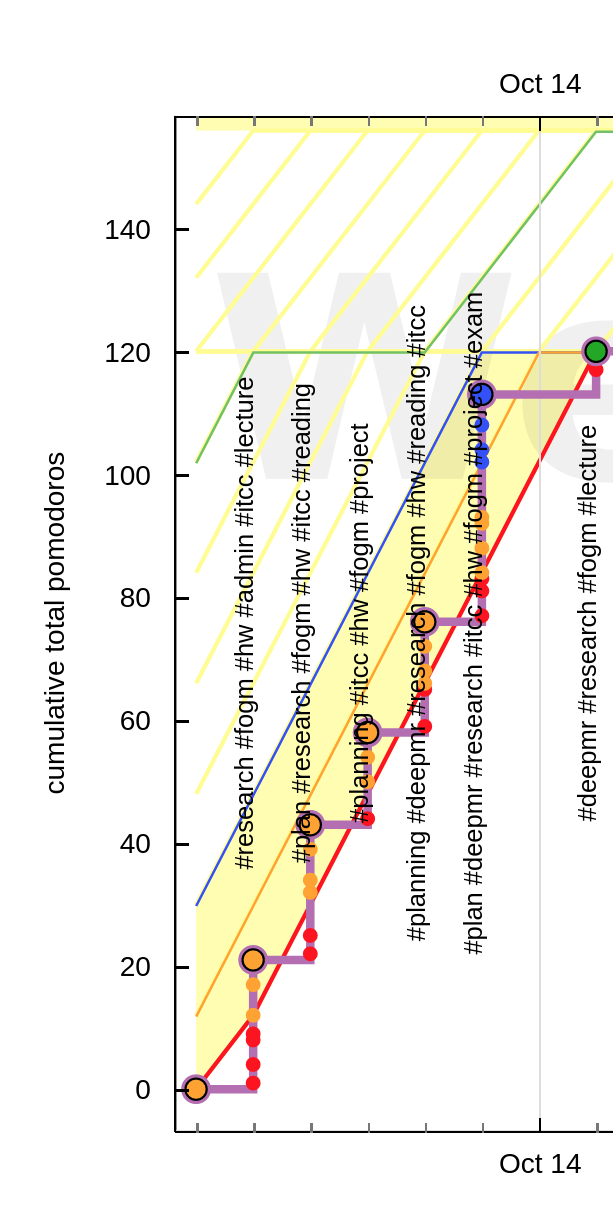

Although I often skipped breaks, I also tracked Pomodoros as promised, averaging 18 per day as shown by the below screenshot of my Beeminder goal.

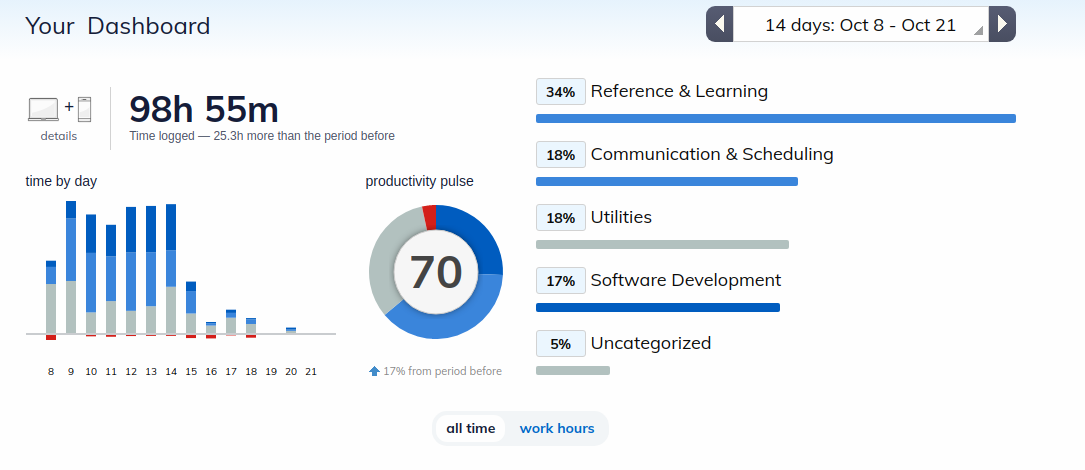

Finally, my RescueTime stats for the past two weeks are below. I kept trying to find a way to only plot the days during the experiment but RescueTime seemingly doesn’t support querying arbitrary time windows. Thankfully, I got a new computer on the 16th and forgot to install RescueTime on it. So as you can see, the only additional time logged outside the experiment is the few hours I spent on my phone and old computer.

Sleep #

I tracked sleep for the first 3 nights and slept 6:45, 7:00, and 7:17 hours respectively. I forgot to keep tracking sleep as the week went on but also know that I ended up sleeping within my normal range every night (between 7 and 8 hours) so I don’t think there’s any insight to be had here anyway.

Mood: Before & during #

In the week prior to my experiment, my mood level averaged 6.31, compared to 6.54 during the experiment. Conclusion: There was no meaningful difference in average mood before and during the experiment.

As an aside, I consistently struggled to decide mood ratings. As someone who’s been known to erupt in fits of cursing while coding and then quickly flip to reciting Kanye lyrics upon solving whatever problem drove me to rage, I expected my mood ratings to be all over the place during the time I spent coding. What I didn’t account for was that these moments make up a relatively small fraction of total work time, so random sampling rarely happens during their occurrence. Instead, when asked by my mood app for my mood, I typically felt nothing. Not in the cold, emotionally dead, repressed action hero sense but rather in the “I feel totally fine but not much emotional affect so let’s say 7 and move on” sense. I wish I had some sort of insightful conclusion to take away from this but it actually just made me pessimistic about the value of tracking mood via self-reports.

Rules & Restrictions Compliance #

I successfully followed all of the restrictions I described in the prior post, with the minor exception of occasionally checking email more than 3 times a day.

Observations #

During my experiment, I aggressively wrote down my thoughts (1)An early reader commented that they imagined “aggressively wrote down my thoughts” as me furiously typing “I AM ELATED!” over and over again, the image of which I found hilarious. The following sections include a combination of after-the-fact observations about the experiment and cleaned-up versions of things I wrote down during it.

People conflate urgency, excessive context switching, and working a lot #

Although I worked more than usual during my maniac week, the work I did felt less urgent than usual. Since I knew I had ample time to get things done, I didn’t rush to complete things and sometimes even did things less efficiently but in more depth than I normally would. As part of my probabilistic ML homework, we had to write a Gibbs Sampler from scratch. Rather than just jotting down some algebra on paper, I wrote up my derivation in Roam in prose so that I’d have something to refer back to in the future. Similarly, I spent more time than I normally would verifying some claims I ran into as part of my research. Counterintuitively, spending more time on individual tasks and sub-tasks reduced their aversiveness. My takeaway from this is that I should be wary of applying Parkinson’s Law to my work in the micro. While I still endorse the value of deadlines for avoiding rabbit holes, I am surprised to only now learn that I seem to be the type of person who gets drained by an overly coercive approach to finishing things.

Related to that, because I avoided internet distractions and checked email ~3 times a day, I context switched even less than I normally do. Through this, I observed how focusing on one thing for long periods of time with minimal interruptions doesn’t produce the same type of tiredness as excessive context-switching does. Describing this quickly runs into the issues of words failing to capture qualia, but the best way I can put it is as follows. Mental clarity is surprisingly orthogonal to mental stamina and hard focus drains stamina but leaves clarity intact, whereas excessive context switching destroys clarity, replacing it with fuzziness. Because I did almost no context switching, I ended my days tired but clear, a state I much prefer to fuzzy.

The combination of a lack of urgency and of context switching enabled me to work 11 hour days while, as mentioned above, having better-than-pre-experiment average mood levels and generally feeling upbeat during the experiment. I hope to try and carry some of these insights about what actually drains my energy by:

- Using deadlines to guide planning but not to motivate speeding up on individual tasks except where absolutely necessary.

- Avoiding context-switching as much as possible.

Working a lot is a great way to get your brain to generate ideas #

While I didn’t track this systematically, I’m pretty sure I had a lot more ideas for potential projects, tweets, and other schemes than usual during this week. As a result of the combination of occasional boredom and lack of stimulation from the internet, ideas seemed to just pop into my conscious randomly. This fits with what I’ve read elsewhere (although I can’t remember where at the moment) that the best way to solve problems is to put yourself in a situation where solving the problem is the alternative to an even more painful activity.

Distractions are surprisingly transient #

During my experiment, I wrote down as many distracting thoughts as possible. Early on, I’d be surprised by what popped into my head, but as time went on, I realized that my brain essentially just loops through a list of people and sites that serve as minor dopamine hits when I get bored. Writing each distraction down made this loopiness especially clear.

I also noticed a similar phenomenon to what Alexey Guzey has mentioned. My temptations to visit a distracting website or check up on a person’s recent work typically disappears within a minute of appearing and doesn’t recur or lead to any residual disappointment. This makes me think that the meditation people are right in claiming that learning to notice distractions is a key skill in staying on task (I guess this is really my bastardized version of their conclusion).

Even “only” 11 hours leave little time to do other things #

As Brent Yorgey observed during his maniac week, an 11 hour work day leaves surprisingly little time for other things during the day. In addition to trying to exercise almost every day, I was dogsitting during my maniac week, meaning I had to walk dogs twice a day for 30 minutes each time. This left around 2 and a half hours for everything besides exercising and dog-walking, essentially eating, reading, and occasionally communicating with other humans. While I didn’t mind this for a short period of time, I think this would be the hardest part of sustaining a schedule like this continuously (especially if weekends were included).

Cartesian dualism is dead; long live Cartesian dualism #

Meta: This really deserves its own blog post but I’m sticking it here.

I often joke my version of Nietzsche’s “god is dead” quote, is “Descartes is dead, we killed him.” By this, I mean that most people in my tribe intellectually accept that the duality between body and brain is false, yet mostly ignore it in every day life. This ignorance manifests as people ignoring their health and assuming it won’t affect their ability to think, not realizing when their mood shifts purely due to biological factors like hunger and tiredness, and not worrying about things (that I of course incessantly worry about) like head injuries.

That said, the point of the heading is not just that people are Cartesian dualists in practice. It’s that a little Cartesian dualism is actually a good thing! Obsessing over health to the point of hypochondria leads to paralysis. Assuming you can only get work done if you’re perfectly well-rested and fed leads to low productivity. Unifying these failure modes is our total inability to introspect accurately and it seems like the best way to avoid is to be a little dualist.

In this vein, my experiment helped realize that I’d naively accepted my introspective assessment of my own abilities and artificially limited myself as a result. I internally feel strongly affected by lack of sleep and/or tiredness, and previously used this to justify not working on hard math-y things when fatigued or sleep deprived. Continuing to work on my CS theory problem set on the day when I slept poorly during the experiment showed me that I can in fact make progress when fatigued and/or sleep deprived. It’s slower than if I were well-rested, but it’s still enough to be worthwhile.

Long live Roam Research #

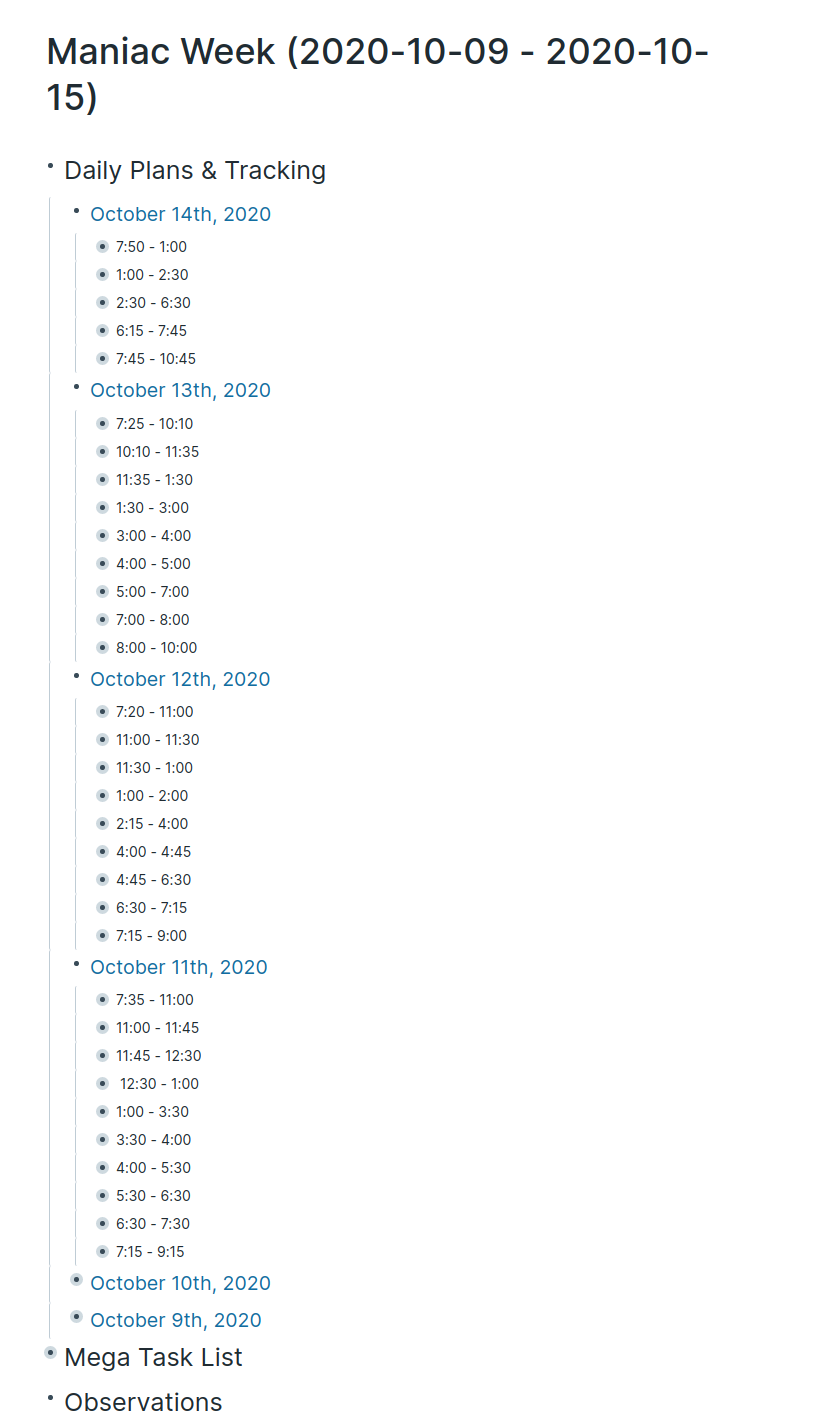

As a heavy Roam Research user, I used Roam to plan my days, track all my tasks, and jot down random thoughts I had during the experiment. Having a clear plan for each day that I could follow by default but easily adjust depending on my energy levels made it much easier for me to keep going.

Conclusion #

Given all of the above, I’d definitely try another maniac week. I’d be curious to try doing one for a more focused goal rather than the three-pronged effort this one consisted of, although I suspect not being able to switch topics would make sustaining focus harder.

Acknowledgements #

Thanks to my girlfriend, Matt Ritter, Alexey Guzey, and Milan Cvitkovic for reading drafts of this post.

Feedback #

I did my best to include observations if and only if others would find them interesting, but if there are things you were curious about that I didn’t discuss, please let me know! Or, if there were things I included that you found especially boring, you can let me know about them too.