Book Review - Elmer Gates and the Art of Mind-using

Table of Contents

Introduction #

Generally when someone tells you they’ve invented an “art of mind-using” that involves lots of made-up words and comes packaged with a spiritual philosophy, you should tell them “no thanks” and walk away. But, what if that same would-be crackpot was also an incredibly successful inventor whose contemporaries considered a genius? Moreover, what if that would-be crackpot also ran careful, rigorous experiments to validate their theories? And so we have Elmer Gates.

Elmer Gates and the Art of Mind-Using (EGAMU) is one of the few books that I simultaneously find incredibly interesting and incredibly hard to read. It interests me tremendously because, as I’ll get into later, I genuinely think Gates had unique insights into the learning and discovery process. But it drives me nuts because the writing is terrible. Gates’s son, Donald, wrote EGAMU as a way of trying to spread Gates’s ideas but unfortunately he and his father share an infuriating writing style. In fact, part of what prompted me to finally finish this review is that I’d like to introduce people to Gates’s ideas but can’t bring myself to suggest people read either EGAMU or his actual writing. Making matters worse, the closest thing to a secondary source on Gates’s ideas is the Elmer Gates website, which I’m incredibly grateful to Lee Humphries for making. That said, most of the useful stuff on there is also written by Gates. Humphries’s short piece on Gates’s method is still the closest thing to an intelligible summary but Humphries understandably leaves out a lot of detail.

In this review, I hope to do my part to remedy this situation by describing Gates, his ideas, and his method in a little more detail such that people can evaluate them without wading through his unintelligible writing.

Biographical sketch #

Elmer Gates was born in 1859 in Ohio. Like many crackpot-geniuses, Gates had an unconventional childhood experience. His education looked a lot like how I imagine a homeschooler’s utopia, private tutors and laboratory to boot. Relevant to the recent debate, in Gates’s case, his environment undoubtedly contributed to his pursuing a highly original path. On one hand, Gates’s access to a private laboratory and specialized tutors allowed him to go far beyond what people learned in school:

Elmer Gates had been at work in his own and different way since 1872, at age thirteen. At various times and for a number of special researches he had in his private laboratories specialists from whom he learned the particular knowledge and skills in various technical arts and techniques in physics, physiology, psychology, chemistry, microscopy, bacteriology, and other fields in preparation for his serious work. Gates’s teachers didn’t just teach him how they wanted to though. They indulged his strong anti-authoritarian streak and desire to study in line with his intrinsic tendencies. However, as corroborated by letters and diary notes, owing to a deep-seated prejudice against authorities of all kinds and a deep- seated instinct, he insisted on being taught from nature rather than from books, and this so agreed with the judgment of his governess- teacher Virginia that she enthusiastically adopted that pedagogic principle. His description of this enviable method follows.

It was his intense wish to have his teachers follow the bent of his mind’s tastes and insights rather than of their own. So definite and dominant was this trait that he invariably refused or failed to follow lessons otherwise forced upon him. His mind would rebel from a lesson it did not want at the time, just as surely as his appetite would rebel from food it did not want. Later in life he felt sure that this strong trait saved him from having all that was most original in his mind squeezed into the narrow and distorting mold of some ordinary creed or curriculum. It was his desire—and his teachers carried it out-that whenever in the course of daily life his attention was at- tracted to, and absorbed in, any object or event, he was then and there to have a lesson upon that subject.

This also left him a lot of freedom to focus on and experiment with both learning methods in addition to actual science. As a result, during this time, Gates became interested in what he’d later call “mental method” and began to develop his unique approach to learning new fields. The insights he made into the operation of the mind later became a key part of his “art of mind-using.”

An early glimpse into his final line of work brought the realization that the experimental methods of science could be applied not only to the introspective study of judgments and morals but also to the de- velopment of an art of mind-using-an art that would give to ordinary minds more and more of the capacities of genius and talent. The idea that there could be a “scientifically determined method of mentating was a gradually dawning glimpse into the promised land of highest hopes.”

Gates’s scientific research & inventions #

While Gates viewed spreading his introspective and mental methods as his primary goal in life, he was equally famous amongst his contemporaries for his interesting research and prolific inventing. Gates invented various devices in the fields of x-rays, electronics, weaving, and more. He also did what we’d now consider a mix of psychology and neuroscience research, much of which bordered on mad science (certainly reflecting the lack of IRBs at the time).

As described in Psychology, Psychurgy, and the Kindergarten, Gates’s research into the operation of the mind involved callous but fascinating experiments on animals. Having observed how his own mind adapted to repeated stimuli, Gates set out to test what we’d now describe as a theory of neural plasticity. First, he ran an experiment on 6 dogs where he trained two dogs to distinguish red vs. green, two to discriminate between shades of red only, and two to distinguish between all the colors. Upon dissecting their brains (as a dog lover, this part gets me), he found that the dogs trained to discriminate all colors had more cells in their visual cortex than those only trained to discriminate red vs. green, and that the red vs. green dogs had more cells than the red only dogs. This provided strong evidence for Gates’s theory that learning drove changes in brain structure, providing evidence for his idea that knowledge had to be embodied in the brain. While this may seem obvious to us now, it’s important to remember that Gates was running these experiments in the late 1800s. X-rays either hadn’t been or were just discovered (in 1895) and Einstein hadn’t yet published his ground-breaking paper on relativity.

On the other hand, unless they some of Gates’s animal experiments either hold up less well or reflect some still-not-understood means of Lamarckian inheritance of complex traits. In the following, Gates describes experiments in which he’d train animals to improve at some task and then measure the skill in their offspring.

I do not know by what mode of reasoning he supposed cutting away part of an organism was able to affect the power of transmission. I took white mice for my experimental subject and instead of cutting off their tails, I trained them in the use of their tails as prehensile apparatus, trained them in the use of their tails as touch-organs and in the feelings of the cold temperature sense and warmth temperature sense, and the fifth generation were born with larger, stronger, longer tails and with the corresponding parts of their brain better developed and with greater sensitiveness to touch and temperature. I trained guinea pigs in the use of the seeing-functions for five generations, according to a method that has been widely published, and the fifth generation waa born with more brain-cells in that part of the brain than any guinea pig of that species had ever before had, and at an early age they could make sight-discriminations that were impossible to other guinea pigs of the same species. This has proved that acquired characteristics can be given to an animal and, also that these characteristics can be transmitted.

I’m honestly not sure what to think of these experiments. My prior is that Lamarckian inheritance doesn’t happen in the realm of complex traits (“complex” is what I’m using to exclude Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance). This leads me to assume that Gates was somehow performing hidden selection that he mis-attributed to Lamarckian inheritance. On the other hand, ethics aside, the results sound simple and definitive enough that successfully reproducing them could result in quite impactful results relative to the average animal experiment.

Gates also ran less ethically dubious experiments on humans to understand and illustrate how to develop what he called “volitional training”. In Can will-power be trained? Gates discusses his experiments training humans to apply finely scaled degrees of muscular force and recognize finer and finer differences between them. As he describes below, Gates’s real goal here was to provide evidence for the general idea that will could be trained by showing results for the simplest possible application.

I will describe the training of volition as related to one of the simplest acts of out mental life; as, for instance, the volitions connected with the willing of a definite muscular motion, such as moving an arm while pulling a cord against a yielding resistance; as, for example, in the chest weights used in gymnastics. If I wish to make a series of parallel lines in a blackboard, by free-hand motions, I must hold in my mind an image of those lines and an idea of what I wish to accomplish; and I must will each separate volitional motion, and the success with which I am able to produce straight and parallel lines depends, not alone on the correctness of my images, concepts, and ideas of what I am trying to do, but also upon the skill with which I am able to direct the separate volitions which make these muscular motions. That is, each volitional element and its accompanying muscular motion must be trained by practice to perform the thing intended. To make a line slightly thicker or thinner, shorter or thinner, depends upon nice [i.e., precise] mental discriminations and volitions, and not upon inanimate physical processes. I have not by any means attempted to discuss the subject of the relation of vitality to mentality; I have only indicated that muscular skill depends upon mental factors, and that volition can be trained, and now I will prove it.

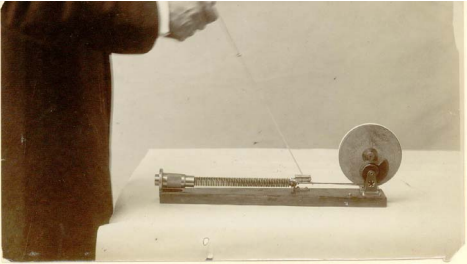

As part of this, Gates invented a new instrument (pictured below) called a “myergesthesiometer” to enable the required training of consistent applications of precisely controlled degrees of force.

Gates’s experiments here were seemingly a resounding success, finding that pupils could learn to distinguish and apply smaller and smaller differences in muscular force by practicing at their current limit for approximately an hour a day. In his own words:

Before such training, this pupil could make a motion with a given degree of energy, and then, when asked to make another motion with the least additional degree of energy, she could not, after repeated trials, will muscular motions involving energy-differences of less than four per cent. But after six days’ practice on an earlier form of Myergesthesiometer, she could make muscular motions involving energy-differences of less than two per cent. Now, it is obvious that one of the elements of skill in the use of muscles in any freehand or manual movements is the mind’s power to discriminate slight energy differences.

As an aside, given the speed at which Gates claims to have observed results, this experiment seems like another good opportunity for someone to reproduce one of Gates’s claims. These results also seem relevant to the modern interest in the boundary between fixed and trainable skills. Deliberate practice believers like (the late, sadly) Anders Ericsson have consistently argued that many skills we don’t believe are trainable can be trained to much higher levels if only we knew the right methods. These and some of the results discussed in the next section, especially if reproduced, could provide additional evidence for these claims.

Gates didn’t limit his experiments to psychology and neuroscience. Although still with the ultimate goal of understanding “mind”, he ran biology experiments studying artificial selection in plants and experiments in other fields, many of which are described in articles linked on the Elmer Gates website. However, I personally found the psychology & neuroscience-flavored experiments the most interesting given how far our understanding of the other fields he studies has advanced since his time.

Gates’s “Art of mind-using” #

Despite being wary of falling into a meta trap (see also), I have to admit that what got me and ultimately kept me interested in Gates’s life and theories was how he’d seemingly systematized learning and discovery. As I’ve written about previously, becoming a deeper, more generative thinker is ongoing goal of mine and so Gates’s purported systematic method for doing so is insight bait for me. And unlike many who peddle theories of learning and idea generation, Gates proved his ability to invent new things across a wide range of fields time and time again. While this gives me confidence that Gates’s techniques at least worked for one person, him, it’s impossible to know how well they generalize to others. For this, we can only rely on priors and his arguments for now. Part of the reason I’m writing this review is because I’m interested in seeing other people assess Gates’s arguments and potentially experiment with some of his techniques.

As I’ve already mentioned, Gates viewed his primary goal in life as understanding how the mind comes to understand things and develop new ideas. Via self-experimentation initially and later via testing his techniques on students, Gates developed a theory of “brain-building” and art of “mind-using”. The former centered around the idea that the mind adapts to its input and embodies all learned contents and skills structurally. The latter revolved around techniques for building up knowledge of sciences and other fields.

Gates’s “mind-using” strategies look very different from modern and traditional learning practices. Gates’s theory of “brain-building” fused radically empiricist and inductivist philosophy with a belief in the mind’s adaptability, and his “art” reflects that. Early on in his studies, Gates observed that acquiring the right higher level concepts depended heavily on having the right foundational experiences. Hence, to learn a new scientific field, Gates would start by gathering the “sensory experiences” that constituted the raw data of that science. In the case of mechanics, this might involve replicating key experiments related to things like gravity or fiction. In the case of chemistry, Gates supposedly replicated the experiments described in multiple textbooks himself. In the case of weaving, which Gates was once challenged to apply his method to (which he did successfully, inventing multiple new devices), we have the following quote regarding how Gates’s went about the initial steps:

I secured letters of introduction to practical weavers and loom makers, and with the aid of several assistants made a systematic search of the technical literature. By actual observation of looms and methods of weaving I built over my brain with reference to that subject; acquiring an the images, concepts, ideas, and thoughts that six weeks’ continuous effort made possible.

Once Gates had had the necessary sensory experiences, he’d move on to the next step of “refunctioning” them. Refunctioning (coined by Gates) refers to mentally reviewing the experiences and observations acquired from the science until they “became more vivid, much more clearly minted and complete, while the processes of states acquired much greater celerity and efficiency.” As far as I can tell, Gates would then move on to repeating the process but for images, concepts, and thoughts (higher levels of abstraction) that emerged from repeatedly reviewing the raw experiences and studying their relationships. The following passage contains the best description I could find of this part of the process:

Then he related each concept to the others, which gave many new and true ideas (to be temporarily recorded until experimentally verified). Every new concept always implied a number of new ideas; and for the first time, to relate new concepts was always a rich opportunity for new ideas.

Outside of this, Gates doesn’t describe the subsequent stages of refunctioning in much detail, so they remain somewhat mysterious to us.

Gates states that this process consistently produced a “functional dominancy”, a state in which the refunctioned experiences, images, etc. take over one’s subconscious and drive it to new ideas and insights about the domain. Gates’s functional dominancies sound similar to the states many creators and discoverers describe as preceding big insights. Michael Nielsen’s Using spaced repetition systems to see through a piece of mathematics contains a fantastic description of this experience, which I suspect strongly resembles Gates’s “functional dominancy”:

Typically, my mathematical work begins with paper-and-pen and messing about, often in a rather ad hoc way. But over time if I really get into something my thinking starts to change. I gradually internalize the mathematical objects I’m dealing with. It becomes easier and easier to conduct (most of) my work in my head. I will go on long walks, and simply think intensively about the objects of concern. Those are no longer symbolic or verbal or visual in the conventional way, though they have some secondary aspects of this nature. Rather, the sense is somehow of working directly with the objects of concern, without any direct symbolic or verbal or visual referents. Furthermore, as my understanding of the objects change – as I learn more about their nature, and correct my own misconceptions – my sense of what I can do with the objects changes as well. It’s as though they sprout new affordances, in the language of user interface design, and I get much practice in learning to fluidly apply those affordances in multiple ways.

Nielsen’s description of working directly with the objects of concern sounds a lot like how Gates describes images becoming more “vivid, clearly minted, and complete”, although personally I find Nielsen’s description much clearer. This is notable because the practice of Ankifying atomic mathematical units related to a proof doesn’t look all that different from Gates’s “refunctioning” if you squint at both.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Gates himself credited his study of how geniuses of the past invented and discovered for inspiring many of his techniques.

It was during this period that Gates began his study of the mental habits of inventors, discoverers, and thinkers of the past from their biographies, and of those of the present by personal interrogation and observation. He experimented “in many machine shops, workshops, studios, offices, instrument stores and manufacturing establishments; studied professional men and women, skilled laborers, talented people and geniuses; artisans of all kinds and races engaged in their skilled trades or vocations.” In the light of his experience and psychologic principles he collected and systematized whatever was normal and best in their mental habits and methods. He investigated carefully over one thousand people of extraordinary minds who, in no single instance after a discovery or invention, did not at once proceed to violate some fundamental psychologic or physiologic law of further success.

He never met investigators who were in surroundings that favored efficient work. When questioned about their mental methods, these investigators were at a loss to describe them, never having thought about their work in that manner. Most dwelt on theories and hypoth- eses and statements that might or might not have been true. It was therefore necessary to rely mostly on the only mind to which he had direct access-his own. This study continued in a lifelong interest in the habits of workers of every kind; Gates could talk to anyone and find common ground and learn something about that person’s work.

Gates took inspiration from strategies past scientists and inventors had haphazardly employed but found that none of them had systematized their strategies. A zealous proponent of Gates’s techniques might even argue that Gates’s techniques are to learning and invention as the Fosbury flop was to high jump. But this also might be going a step too far given the lack of subsequent reproduction of Gates’s successes to date.

In spite of Gates’s methods’ superficial difference from modern educational practices, I think his methods ultimately draw on the same insights as do the forms of training described extensively in the deliberate practice literature just applied to learning and idea generation. Viewed through the lens of cognitive science and skill development research, Gates’s method seems like a way to speed up and optimize chunking of scientific knowledge. Nielsen’s essay also include a helpful description of chunking:

In retrospect, I think that what’s going on is what psychologists call chunking. People who intensively study a subject gradually start to build mental libraries of “chunks” – large-scale patterns that they recognize and use to reason. This is why some grandmaster chess players can remember thousands of games move for move. They’re not remembering the individual moves – they’re remembering the ideas those games express, in terms of larger patterns. And they’ve studied chess so much that those ideas and patterns are deeply meaningful, much as the phrases in a lover’s letter may be meaningful. It’s why top basketball players have extraordinary recall of games. Experts begin to think, perhaps only semi-consciously, using such chunks. The conventional representations – words or symbols in mathematics, or moves on a chessboard – are still there, but they are somehow secondary.

So rather than develop chunks haphazardly, Gates discovered a way to have them emerge systematically and (allegedly) more quickly than the typical education system.

We can also compare Gates’s strategies to central examples from the deliberate pracitce literature such as chess training (famously studied in Chase & Simon’s classic paper from 1973). It turns out that Gates’s method isn’t all that different from the way that chess players study positions from past games to improve their skills. Instead of positions, Gates used sensory data from scientific experiments and then applied a slightly more introspective bent to things. (1)Early studies of chess players provided foundational evidence for much of chunking theory. In their work, Chase & Simon studied expert chess players’ abilities to memorize board setups after only seeing them briefly. At the time, some people believed that these abilities came from these players possessing generically prodigious memories while others believed the ability would be limited to chess. Chase & Simon constructed a clever experiment to test these two hypotheses by presenting expert & novice chess players with real chess game board positions and random board positions and measuring their ability to reconstruct the positions after they’d been removed from the board. As the below plot of number of recalls required to reconstruct positions correctly shows, the experts required meaningfully fewer trials to correctly reconstruct the real positions but performed nearly identically to the novices on the random positions.

Finally, Gates’s methods have an eerily resemblance to modern machine learning training, in particular un-/semi-supervised learning methods. Gates’s method involves gathering a set of good sensory experiences (data) and repeatedly passing them through one’s internal sensory theater (network) in order to develop better representations of them. Modern semi-supervised, multimodal learning looks quite similar except it usually involves an explicit prediction task. If nothing else, having long ago asked a question on HN regarding whether we can learn anything about human learning from self-play techniques in ML, I feel slightly vindicated at observing even a tenuous connection.

So far, I’ve mostly treared Gates’s method favorably. And to be clear, my all-things-considered view is that Gates’s ideas and results are intriguing enough to warrant testing by others, especially given said testing can be done by individuals and is relatively cheap. That said, Gates isn’t the first person to claim they’ve got an introspective technique that turns people into geniuses and the reality is that Gates’s results haven’t been reproduced by anyone in the ~125 years since he lived. So I recognize there’s a lot to be skeptical of here.

What follows is my attempt at steelmanning the good faith but unconvinced skeptics’s case against Gates’s method being worth testing more. Gates’s inventions were definitely impressive but many geniuses had interesting ideas and invented cool things. Despite that, the claim that Gates found a systematic method for compressing learning a field seemingly by orders of magnitude and then enabling consistent novel discoveries is an extraordinary claim that requires extraordinary evidence (Todo: link).

Instead, all we have are Gates’s and his son’s own claims about these methods working for Gates and some of his students, whom we know nothing about. As evidence against Gates’s claims, we have decades of learning research suggesting that learning speed can be improved but not by nearly as much as Gates claimed. Taking the example of chess players, while the connection between Gates’s method and theirs is reasonable, chess player training takes much longer than Gates claimed to spend on an entire scientific field.

To summarize, while there’s nothing wrong with some people trying Gates’s methods, we lack even close to sufficient evidence to assign even medium credence to Gates’s claims about the efficacy of his methods.

Putting my “actual me” hat back on, I agree with several of the hypothetical skeptic’s points. I agree that our prior should be that geniuses don’t have generalizable methods and that the connection to chess player training suggests skepticism about the magnitude of Gates’s claims. Ultimately though, I still disagree with the hypothetical skeptic about how unlikely finding low-hanging fruit for improving discovery is and about how little weight we should assign to this form of n=1 evidence. On the first point, while I acknowledge the existence of the learning literature, when it comes to education, most of it focuses on improving average or median outcomes, which is going to look quite different from trying to improve performance at the tails. On the second point, as much as I find Gates’s and his son’s style frustrating, reading about his actual introspective experiments leaves me trusting his results enough to assign non-negligible credence to them being reproducible if tried and iterated on. I don’t really know what underlying beliefs lead to this but it seems important to state outright. (2)It’s also very important to note that to the degree I endorse Gates’s ideas, it’s the specific ideas I discussed in the post. Gates had many other ideas, which I strongly disagree with and didn’t discuss in the post. In particular, Gates had a bunch of more teleological ideas about the purpose of humanity and the mind that I find outright silly.

To try to keep this relatively short, I’ve focused on what I consider the core of Gates’s mental method. However, as you might expect from a mad scientist focused on introspective methods, Gates employed other interesting auxiliary techniques in his quest to develop his mind. At one point, Gates decided to inventory and categorize every memory he could recall from his entire life. EGAMU describes this as follows:

He felt the foreglow of a new step, and under this impulse and leading made a comprehensive inventory of every experience he could remember or introspectively notice, systematically recorded under its proper heading of sensory, intellective, introspective, esthesic, or conative. The good or bad of his life, every reprehensible or laudable act, was impartially studied. No other experience of his early life contributed more than the one simple trait, learned perhaps mostly from his tutor Virginia, of looking at his mind and work with the im- partiality of a third person and thus eliminating much personal bias.

In several thousand pages, conveniently classified, he recorded all he could remember of his experiences with or about stars, plants, animals, minerals, chemicals, mechanics, literature, language, math- ematics, logic, history, fine arts, religion, and everything else. His total vocabulary was included, as well as all experiences with emotions, such as those relating to parents, friends, schooldays, social events, angers, griefs, joys, laughter, amusements, and all things he had made and done. He was amazed not only at the magnitude of his inventory but equally at the vastness of what he did not know about each sub- ject.

It was a long and tedious task. Many times when certain portions were considered complete he would recall additional incidents. Maybe it was a book read long ago, or a slight illness or visit or conversation or a walk or a dream-and it was a task to record all that could be slowly and indistinctly remembered. Maybe it was an early acquain- tance who was hunted up and interrogated for assistance in recalling a that had taken place between them; or perhaps the only clue was some scrap of paper or part of an old letter. Sometimes by repeating a walk or trip, things and places could be recalled… or rereading books or repeating experiments. He found it peculiarly difficult to recall with sufficient definiteness to state them, the emotive pleasures, pains, and sorrows of earlier life.

Gates also described a method for (allegedly) enhancing foundational mental capacities that he called “dirigation”. Similar to his other introspective methods, dirigation resembles meditation but focuses on more practical outcomes. Dirigation revolved around directing and maintaining attention to specific regions of the body or brain to drive growth and enhancement of them. Gates’s proof-of-principle dirigation technique was training people to dirigate to one of their hands until its blood volume grew, which could easily be measured by submerging the hand in a full bucket of water and then observing the bucket overflow. According to Gates, consistent practice at this form of dirigation could strengthen the target body apart or area:

Regular dirigation augmented the growth of a bodily part. As an example, a patient who was taught to dirigate was able to increase measurably the girth of one arm. Also abnormally small organs could slowly be increased in size, and it became evident that dirigation had applications in curing certain diseases and underdeveloped organs, as well as in training the attention. It was not difficult, after sufficient practice, by dirigation to produce emesis, catharsis, enuresis, saliva

Gates used this same method to allegedly augment both sensory and purely mental skills and capabilities.

Gates then found he could shift the dirigative dominancy from sensating to imaging, and thus he gradually learned to dirigate to the cortical image areas of each sense; and from that state to dirigative control of the higher intellections, such as conceptuating, ideating, and thinking. This practice was an aid to intellection, rendering the function more alert, active, quick, and intense. One or two days’ practice enabled him to render dominant and fully active any one of the intellectual powers, and its work was then done more easily, quickly, and accurately than otherwise. This dirigation was extremely difficult because at first he could not locate the function anatomically. A process like ideating or thinking has not a definite center but consists in groups of cells and fibers and ganglia scattered variously throughout the cerebrum and subcerebral nervous structures. After long effort he could dirigate to a functional activity as soon as it could be distinguished from all other kinds of functioning. This he discovered how to do in two ways: by overworking that function just enough to feel slightly the prodromata of its fatigue; and by rapid alternation of different kinds of functions, as first the arithmetical, then the musical, changing rapidly until its unique distinction between the feelings was identified. The local sign was not necessarily the feeling of a bodily part but of an activity that differed qualitatively from other activities. Dirigation to the mental activities concerned with mathematics, for example, augmented ability in that line and increased the fruitfulness of new ideas

Gates described dirigation to more complex targets as well:

But a better result was obtained when he finally dirigated to the mutual modification of all factors that resulted when they were simultaneously acting in the synthesis of the conation. He cited as an example shooting at a target with bow and arrow: the process was repeated in close succession until he located the feelings accompanying that conation as a whole, including the feeling of the whole bodily attitude, every muscular strain, and every mental operation.

Gates even claimed that dirigation could help with mood and behavioral change:

A pupil could be taught dirigatively to functionate all the happy esthesias more often in a single week, and get a fuller acquaintance with them, than he would normally in years of ordinary life. By this means the tide of life’s energies will be augmented, and every mental capacity and activity increased, Gates pointed out. Emotive dirigation had many times enabled him to “keep sorrow in abeyance and worry at arm’s length.”

However, Gates warned that dirigation could produce strikingly vivid imagery that one had to be careful to not overly encourage:

If dirigation was intense, frequent, and prolonged it produced a functional hyperesthesia that aroused images of more than usual vividness—a “dream-like” vividness and a self-active sort of spontaneity that was less subject to volitional modification than the memorial images. If these dreamlike images were dirigated to with sufficient intensity and frequency, there resulted not only an increased hyperesthesia but also a vasomotor surcharging of the functionally active organs, producing a hyperemia that created something still more vivid, phantasms, which were so seemingly real and so little susceptible to modification by voluntary effort that they were apt to be mistaken for reality. The image is thought to be an apparition. If this dirigation was continued, the hyperemia would not subside and the phantasm would become permanent, and the result would be delusional insanity, as happens in monomania.

Putting it all together, Gates impresses me as someone who took the idea of deliberate practice for knowledge work seriously. Unlike many who get into meditation or other introspective practices, Gates always tested his “meta” introspective techniques by continuing to invent and discover in diverse fields. And in spite of his quasi-spiritual tendencies, he seemed to take experimental rigor seriously, ensuring he could reproduce his results across his life and occasionally with his pupils. If we had five more Elmer Gateses, I’m confident we’d be much better off for it and know much more about how to improve learning and discovery.

Why isn’t Gates more well-known? #

Relative to famous inventors of the time such as Thomas Edison (born 12 years before Gates) and Tesla, Gates is not well known at all. Part of this is that his inventions were less impressive and impactful, but some other incidental factors likely contribute as well. Gates was incredibly verbose with EGAMU itself running nearly 1,000 pages and the Elmer Gates papers containing thousands upon thousands of pages of diaries and writing from Gates. There’s also something about Gates’s style that makes reading his writing difficult. I struggle to put my finger on it but it’s related to his tendency towards using novel terms of his own invention without examples combined with his interleaving of scientific claims and normative ones. However, many academic fields also coin lots of confusing jargon and don’t provide sufficient examples for laymen to understand, so this doesn’t fully explain why Gates failed to make his mark on history.

Instead, what really seems to have relegated Gates to irrelevance was his inability to build a field around himself. At one point, Gates had a large lab in Maryland and seemingly had at least tens of students. However, presumably none of these students became a true successor. His son understood his work well enough to write EGAMU but appears to have been more of a historian than an actual practitioner of Gates’s methods. And for all the reasons already discussed, EGAMU presumably failed to catch on as a popular exposition of Gates’s ideas. In the absence of a true successor or popular description of his works, we can imagine how Gates’s methods became increasingly unknown.

Where to go from here? #

In case it’s not already clear, I’m very interested in experimenting with some of the techniques Gates describes for learning new fields. Worst case, I lose some discretionary time from a month or two of time that I otherwise would’ve spent learning something. Best case, I discover a new method for learning things that helps both me and potentially others become more knowledgable, generative, and creative going forward. Furthermore, Gates seemed to describe the outcome of this process as incredibly joyous and fulfilling, which I definitely would be happy to experience as a side effect.

If you’re also interested in experimenting with some of these things, please let me know!

Conclusion #

My main takeaway from Gates’s life and work is that there may be much lower hanging fruit than I’d previously believed in trying to improve mental methods for learning and discovery that can come from introspection and practice rather than the traditional psychological paradigm. While we should exercise some skepticism in taking Gates’s results at face value, I think they warrant further experimentation and investigation given the potential impact they could have.

On a different note, I think Gates as a figure embodies a lot of the characteristics people within the progress studies movement at least purport to want to encourage. First of all, he was earnestly trying to understand the world in a way that looked a little crazy and weird from the outside, something some people I know have been talking about us taking more seriously as “real science”. Second, Gates was a private inventor who developed potentially hundreds of useful tools that bettered peoples lives and advanced scientific and technological progress. As far as anyone deserves to be held up as a successful contributor to progress, Gates should make the cut.