Decentralization of Atoms is Underrated

This post was co-authored with Austin Vernon.

Summary #

While the internet often focuses its furious debate energy on decentralization in the realm of bits, in the realm of atoms, decentralization is currently underrated in terms of its feasibility and desirability. New technologies in areas like aviation, freight, and life sciences can and are shifting the scales towards decentralized models being possible. This has the potential to broaden access, reduce costs, and increase individual empowerment.

Decoupling Electricity #

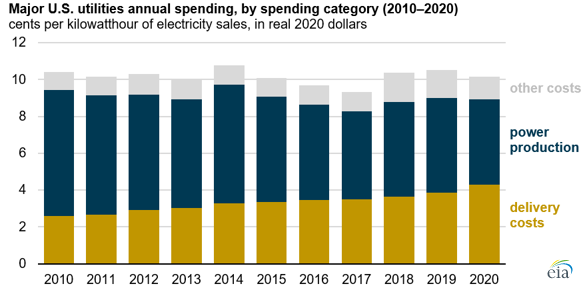

Traditional electricity generation and distribution technologies need highly centralized systems to service customers economically. Virtually all distribution systems and many electricity generators are government-enforced monopolies. Utility captured regulators approve rates, leading to higher costs or preventing costs from falling if new technology emerges. In the US, non-power production categories make up more than half of electricity costs. Solar, batteries, and micronuclear could enable more decentralized electricity generation that competes with monopolies.

Decentralized energy generation through solar panels paired with battery storage limits how high rates can go. Customers can defect if going off-grid or adding solar becomes cheaper. In places like California, where households pay ~$0.25/kWh, many can save money by adding a solar plus storage system. The cheaper solar and batteries get, the more competition utilities face.

Almost a billion people have no access to electricity, and many more suffer from frequent electricity outages. Solar and batteries can provide extra energy where traditional service is failing. Distributed solar is very popular in Puerto Rico, Lebanon, and Afghanistan.

Many cost barriers to distributed solar in the US are related to labor, permits, and integrating components. Residential solar costs ~$1.30/watt in places like Australia or Germany but are >$2.50/watt in the US. The cost difference for larger commercial systems is less pronounced. Streamlining permitting, integrating components into single packages, and continued decreases in costs for the panels and batteries are all important avenues for improvement. Falling component prices will have an outsize impact in poorer places because they dominate the cost equation in countries with lower labor costs.

Small nuclear batteries have a path to be competitive in the future. Solar panels are cheap because they are solid-state devices that harvest radiation from the sun. Maintenance and complexity are low. Small nuclear generators could be solid-state devices that harvest radiation from nuclear fuel. The technology isn’t widely available today, but it is a worthy goal.

Decentralizing electricity production has the power to increase competition and overcome woeful state capacity in a way few other energy technologies can.

Solving Bottlenecks in Transportation #

Transportation is undergoing an electrification revolution. Electric vehicle designs can lower operating costs and use power-dense motors to compete in smaller, more flexible form factors that allow new business models.

Freight Trains #

Freight already undertook a decentralization revolution with diesel trucks. Even though rail is ~$0.05 per ton-mile vs. ~$0.15-$0.20 per ton-mile for trucks, it only accounts for a quarter of ton-miles. Trucks now carry more ton-miles and dominate revenue because they are more flexible, handle low-density routes cost-effectively, and have shorter delivery times.

But, quasi-monopoly rail companies are often the only realistic transportation options for shippers of goods like chemicals, coal, and grains. Freight rates can be high because more expensive trucks are the only alternative.

Electric trucks, especially those with full or partial automation, promise to reduce trucking costs dramatically and increase competition. Wages and benefits account for half the expenses, while fuel and maintenance make up another 32%. Eliminating driver labor and halving fuel/maintenance would make trucking competitive with rail per ton-mile. Automation may not happen all at once, but fixed routes and long highway trips look like promising early applications.

The stiffer competition will force railroads to lower rates and unions to make concessions that allow more automation of conductors and track maintenance teams. Railroads have already invested in positive train control and trialed automated track inspection to cut labor costs, but unions and the aligned Federal Railroad Administration have blocked implementation.

We’d all benefit from lower-cost goods by making decentralized freight as cheap as rail.

Air Travel #

Modern plane engines guzzle fuel and are maintenance intensive. Large aircraft like Boeing 737 and 777 use less fuel per passenger mile than smaller jets and spread fixed costs over more passengers. Airlines hubs exist to increase passenger density and exploit the cost advantages of large aircraft. But customers prefer direct flights, more options, and fewer disruptions like missing connections. Technologies that decrease the cost of point-to-point flights would improve customer satisfaction and reduce door-to-door travel times.

These desires have already led to the increasing use of regional jets and designs like the 787 that make more routes profitable and enable “mini-hubs.” There is a limit where increasing cost kills moving away from hubs. Southwest earns less than fifteen cents per passenger mile with 737s. An airline like Cape Air flying <10 passenger planes charges over $0.50 per passenger-mile to break even.

New technologies could make future small planes surprisingly competitive. Manufacturers have avoided the low-end small plane market for a variety of reasons. Low-hanging fruit like utilizing digital design software and modern piston engines are still available. Otto Aviation’s Celera 500 concept is one trying to fill the gap. It is ultra-aerodynamic and uses a modern diesel engine to reduce fuel consumption by 90% compared to a light jet. There are still many hurdles, but it is an exciting program that could offer private jet experiences at business-class prices.

Electric commuter planes are another option because their motors reduce maintenance and increase efficiency. They can fly out of smaller airports that shorten door-to-door travel times. Batteries limit range but might still be faster than connecting at hubs for poorly connected city pairs, even with two or three stops to charge. Low-demand city pairs could support multiple direct flights per day.

Cost is still a challenge. Models projected to come into service in the mid-2020s will cost roughly $0.35 per passenger mile. High upfront costs and replacing batteries offset fuel and maintenance savings. But these planes will still cost less than driving for single passengers and improve door-to-door times on <400-mile routes where big airliners don’t make sense.

NASA’s analysis shows that cost reductions must come from many categories for a theoretical 9-seat airliner. To eventually match 737 costs, the cost must be <$1.30 per mile, yielding $0.14 per passenger mile. External savings like reducing electricity cost, falling battery prices, single pilot operation, and less conservative maintenance assumptions still leaves passenger mile costs at double our target. Further savings require designs that are reliable, easy to inspect, and simple to manufacture.

The cost to produce an airplane falls rapidly as production increases. Early markets to build scale are critical to unlocking longer-term savings. Commuter airlines like Cape Air are some of the earliest buyers of electric planes. They hope to use the lower cost structure to grow revenue and add more routes. Fractional plane ownership companies like Wheels Up or NetJets could be huge customers for planes like Celera and high-performance electric planes because of the potential to open up their services to customers at lower price points. Like trucks, smaller aircraft could gain market share at a higher price point by competing with convenience and door-to-door time improvements.

The complexity of designing aircraft means a revolution won’t happen overnight, but the future is bright for more decentralized flight.

Cargo Ships #

Vessels like container ships, bulk carriers, and crude tankers see massive benefits from scale. Labor, maintenance, fuel (the dominant cost), and CAPEX costs improve rapidly until a ship holds around 5000 20’ containers, then the pace slows. Massive ships suffer a few drawbacks. A customer’s cargo is in transit longer because of slower loading/unloading and lower frequency trips. And cargo ends up further from end customers because only a few ports can handle the biggest ships. These ports are also more vulnerable to labor strikes and rising fees as their competition decreases.

Like other form factors, electric ships can have comparable economics at a smaller size due to lower maintenance and fuel costs. Smaller ships can use underutilized ports bypassed by large vessels. A shorter range is acceptable because most container ships make many stops and do not go straight across oceans.

Many consider battery-electric ships impractical because carrying enough batteries to match conventional ship ranges would use up all the cargo space. A different way to attack the problem is to containerize batteries, charge them offsite, then load them onto the ship with regular cranes. A theoretical 4000 container ship might use 90 containers of batteries per day, leaving plenty of space for cargo. Most ships use massive fuel tanks that allow them to go a month or more between refueling and only buy fuel from the cheapest ports. An electric ship may not even lose cargo space since it is deleting fuel tanks and ballast tanks while only carrying a few days of batteries.

The electricity break-even price when oil is $80 per barrel is ~$160/MWh. Charging the batteries with grid electricity or onsite solar panels could reduce fuel costs by 50%-75%. If solar panels keep getting cheaper, it might be more like a 90% reduction. Buying/replacing the batteries adds ~$35/MWh for every $100/kWh of CAPEX, assuming 180 cycles per year, 5000 cycles, and a 5% discount rate. Switching batteries often reduces the total number of batteries a fleet needs and depreciates them faster, lowering cycle costs.

There are attractive entry markets for containerized batteries. Some ship types, like oilfield support vessels, already have electric motors powered by diesel generators. The battery containers replace the generator in a relatively low-cost conversion. FleetZero is one startup pursuing this path. Eventually, new ship designs could take better advantage of batteries and beat traditional shippers on cost.

Low-cost ships that fit in many smaller ports prevent one facility, like the Port of Long Beach, from becoming a choke point. Competition between ports will encourage automation and lower costs for loading/unloading ships while delivering cargo closer to end customers. Electric ships could also reduce the damage inflicted by the Jones Act. More shipyards can compete to build smaller vessels. Removing the complex fuel and engine systems reduces the manufacturing difficulty.

Increasing competition across the entire value chain by increasing ship count and improving small port utilization would greatly benefit the US and global economies.

Public Transit #

E-bikes and electric buses are inexpensive, easy-to-implement alternatives to light rail in cities. Innovations like Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) allow light rail throughput with a fraction of the infrastructure, state capacity, and capital cost. Diesel buses already have lower hourly operating costs than light rail. Electrifying them can push their advantage further by reducing operating costs. Adding more priority signaling to increase average speed helps, too. Other modes, like commuter buses, see their cost fall below that of heavy rail. Most cities will take advantage of decreased costs by adding lower utilization routes.

E-bikes allow personal transportation in cities while using a fraction of the space cars require. Protected cycling infrastructure is even simpler than a BRT line. An e-bike costs roughly $0.10 per passenger mile, a single-passenger car is $0.62, and light rail and BRT cost ~$1 per passenger mile. E-bikes are also fast. Light rail travels 16 mph, and BRT is ~10 mph. E-bike speeds can average over 14 mph with good infrastructure, and they don’t require extra travel to stops/stations or waiting. They should continue to grow in popularity and can bypass problems like strikes or maintenance outages that centralized transit systems can suffer.

Enabling faster and more adaptive public health #

Public health efforts start from an assumption of centralized control and coordination. Federal public health officials coordinate with state ones to decide on mitigation strategies such as mobility limitation and vaccination plans. The success of these efforts relies on centralized capacity, agility, and competence which may not exist, struggles to adapt itself to conditions on the ground, and is subject to capture by bad actors. On top of that, the centralized approach depends heavily on manufacturing process knowledge that only a few specialized groups currently hold (or in some cases, think they do but do not).

Vaccines #

Vaccines are mainly designed by academics or pharmaceutical companies and require large manufacturing and regulatory efforts to test and eventually deploy. Because vaccines are considered low RoI and sometimes controversial, they’re underinvested in and often abandoned.

Rapid Deployment Vaccine Collaborative (RadVac) shows the potential of a different vaccine development model. RadVac started as a group of biologists and entrepreneurs who decided to develop their own DIY vaccine after becoming frustrated by waiting but has since evolved into an open source COVID vaccine development collective.

RadVac’s vaccine development follows the open source model of rapid iteration and refinement. Each new version of the design gets shared publicly, manufactured and tested by individuals or local groups, and then iterated on and potentially forked. Contributors report back, feeding into updates that improve the core design, ensure the vaccine protects against newer variants, or make production easier. As of writing, RadVac is on version 5.2.1 of its vaccine design compared to version 2 of the two mRNA vaccines.

Scaling up the open source model would bring additional advantages. Decentralized testing and experimentation could tap into a much larger pool of people than centralized trials, while local tacit knowledge might enable communities to adapt to conditions on the ground much more rapidly than under resourced centralized actors, especially for viruses that adapt as rapidly as COVID.

For newer vaccine platforms like mRNA, manufacturing difficulty is an obstacle to decentralized development. Lipid nanoparticles technology is heavily guarded by patents (fact check) and difficult to get right (link to developing countries). Especially if we want decentralized vaccine development to extend to developing countries, we need vaccine platforms individuals and small communities can work with.

Peptide vaccines such as RadVac’s can be made relatively cheap by synthetic peptides that are easy to order. But with synthesis costs continuing to decline and synthetic biology becoming more powerful (see next top level section), future peptide vaccines could be potentially grown inside cells. Through this or other developments, future vaccine production can potentially be done “at the edge” by communities, enabling more rapid and locally savvy responses.

Pathogen detection and diagnosis #

COVID showed that wastewater captures a lot of information about pathogen prevalence. Expanded monitoring systems could help track community spread and identify novel pathogens much earlier. Combining these systems with rapid vaccine development could supercharge public health responses.

Imagine if every city or town had cheap access to biobots or the NAO that tracked flu, RSV, and other pathogenic viruses, updated daily, and displayed all its information on an aggregate level plus broken down by location. Community members could use this to inform their behavior and invest in (hypothetical) rapid vaccine development or purchasing programs and future Yougang Gus could build better models for predicting spread of disease.

With new technology, this may become increasingly possible. As both long and short read sequencing costs continue to drop and other steps in the process get ironed out, groups like biobots and the NAO can potentially expand their offerings throughout the country and potentially become easier to run.

As with vaccines, realtime pathogen data can allow communities to respond to threats in realtime and react without having to rely on a centralized authority.

Enabling more synthetic biology “hackers" #

As described by its early proponents, synthetic biology offers the possibility of “growing almost everything” or at least much more than we grow right now. As Elliot Hershberg recently wrote, atoms are local and biology is the “ultimate distributed manufacturing technology”. Imagine a world where biology is end-user modifiable, where you can grow meat in your home, hack plants to grow medicines, and potentially one day even grow electronics. This may sound fantastical but consider that you started as a single fertilized egg that assembled itself into a member of the most intelligent species on the planet (as of this writing).

Unfortunately, with a few notable exceptions, synthetic biology is currently inaccessible to most. Hobbyists exist but most real projects still require access to a lab, enough experience to design the genomes, clone and assemble the genes, transfect the bacteria (or other model organism), assay, and analyze the result. Even then, you may not be able to access synthesis and sequencing tools unless you can prove you’re a “legitimate institution”.

This barrier to entry prevents the full promise of “growing almost everything”. As we saw during the computer revolution and more recently with hobbyist hardware, knowledge accumulation accelerates when 10s or even 100s of thousands can develop new products, improve core tools, and contribute these improvements back to the community. While democratization comes with risks, a world in which the population is steeped in biological technology and knowledge is also one in which 100s of thousands of benevolent “hackers” can rapidly design protections and mitigations for emergent risks.

A synthetic biology agenda that focuses on driving down costs, increasing portability, and treating the tools as a product for millions rather than a closely held secret will enable more progress, robust distributed safety, and a more exciting field. A roadmap for enabling this is out of the scope of this essay, but core to any agenda would be continuing to reduce costs while improving the “UX” of key tooling and building out communities of practice.

While sequencing and synthesis will presumably continue to become cheaper and easier to do, other tools tend to get less attention. For example, nearly all big synthetic bio projects require cloning, but cloning workflows often require “magic hands” plus expensive trial and error to get right. This is both a tool and knowledge problem. Researchers mostly focus on building tools that can do new things rather than making existing tools and workflows easy to use and robust. (In contrast, in software, the open source community often fills this gap, building out things like sklearn that make using complicated algorithms much easier.) As a result, are harder for hobbyists to learn unless they’re lucky enough to have access to an expert. As another example, “domesticating” cell lines is famously difficult to do without hiring an expert who’s done it before, meaning most hobbyists have to rely on less effective versions of workhorse organisms than what exists inside a place like Ginkgo Bioworks.

Progress requires a combination of engineering, research, and more efficient means of spreading knowledge. On the engineering side, we need much more work on building cheap, portable, and easy-to-use tooling like OpenPCR and open source microfluidics. Researchers can contribute by discovering ways to simplify or improve the robustness of underlying technology. This could mean replacing thermocyclers with helicases.

As has been written about elsewhere, we can do so much better than papers as a means for spreading procedural knowledge. Courses such as The Odin’s bioengineering courses show how we can take advantage of the YouTube revolution for knowledge transfer to enable people to learn on their own outside the confines of a major academic lab. Meanwhile, new platforms can create incentives to actually share protocols in enough detail for someone to understand as opposed to the often intentionally obfuscatory versions in papers. Projects like the Cultivarium, which “creates open source tools for life scientists to expand access to novel microorganisms”, also show how certain types of research can combine with new models for sharing to supercharge progress. Finally, as Arye Lipman recently proposed, community biolabs can act as “garages” for synthetic bio hackers, thereby helping to build scenius outside of academia.

Better tech, tools, and knowledge dissemination can speed up the “grow everything” vision and help build a self-reliant, distributed, biological manufacturing infrastructure for the future.

Conclusion #

While the technological progress of the past century has led to transformative benefits, it has sometimes come at the cost of decreased agency for individuals and communities. The thread that ties decentralized energy production, transportation, public health, and biological manufacturing together is that they all increase rather than decrease human agency.

Not everyone is in favor of increasing agency. Critics of decentralization point to the potential downsides of empowering individuals and small groups with these technologies. Solar power allows for radical communities to survive off the grid outside the reach of authorities. Personal aircraft and drones can be used for attacks or other malicious goals. Biological manufacturing technologies are famously dual use.

We believe these developments will be net positive, especially with thoughtful risk mitigations. We also view agency as a terminal value that’s important to uphold independent of its potential benefits. A world where individuals have access to powerful technology is a world filled with opportunity.