Continuous glucose monitors (CGM) and beyond: A dialogue

Table of Contents

What are continuous glucose monitors good for? More broadly, what are continuous measures of physiology (CxM) good for?

Similar to Elliot and I’s dialogue, this post has an unconventional format. It’s both a synthesis of Willy’s, Eryney’s, and my opinions on continuous monitoring combined with a debate in places where we disagree. To try and make it clear which views are coming from each person, we’ve annotated sections that come from a subset of us rather than all of us with e.g. “Stephen’s views” or “Willy’s dissent”.

CGMs #

First, a brief explanation of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs). CGMs are devices designed to supplement or replace the frequent blood sugar checks (done with a fingerstick device) that diabetics must perform several times daily. An even briefer primer on diabetes, of which there are two types:

- type 1 diabetes is effectively “insulin deficiency”, caused by autoimmune destruction of beta islet cells in the pancreas;

- type 2 diabetes is “insulin resistance” +/- varying degrees of insulin deficiency.

The former must always supplement with insulin (“exogenous insulin”) to control their blood sugar and prevent ketoacidosis, since they don’t produce enough insulin; the latter, depending on many factors, can often avoid insulin use. Insulin use requires frequent, painful checking of blood sugar levels, a large source of inconvenience for diabetics.

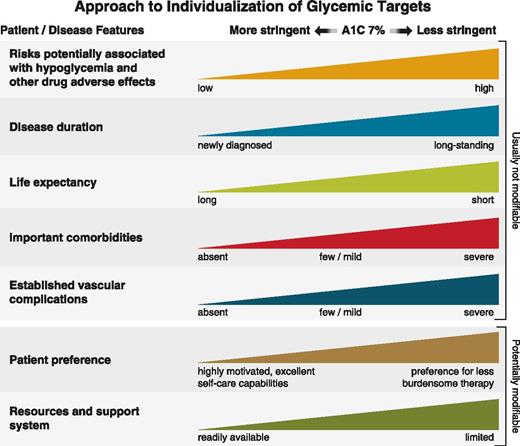

The TL;DR on CGMs from a medical perspective is that they are useful for type 1 diabetics, and appear to allow for a lower average blood sugar level (usually measured through A1C) while avoiding dangerously low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia). Lower A1C, all else equal, tends to predict lower long-term complications of diabetes, subject to many caveats– for example, patients with low remaining life expectancy, like elderly patients or those with multiple comorbidities, are not advised to aim for low A1C, since the cost of getting there (higher rates of adverse effects like fainting from hypoglycemia) is higher, while the benefit is unlikely to be realized.

For type 2 diabetics, there is debate over whether there is any benefit of using CGMs, and many payers (government, insurance companies) place significant documentation barriers to obtaining them (ctrl + f CMS’s policy “to be eligible for coverage..”), especially given their non-trivial cost.

Willy’s view: Enter CGMs for non-diabetics. Tracing this idea to its inception is difficult, but the most visible CGM company in this space is Levels. Why does Levels believe that non-diabetics will benefit from CGMs? Their “master plan” blog post appears to hinge on behavioral change as the key, but also mixes in the possibility that better glucose control in non-diabetics has some impact as well:

Levels helps you see how food affects your health…there hasn’t been a way to quantify how your diet affects you…In the same way that everyone knows to get eight hours of sleep, and how Fitbit convinced people that walking 10,000 steps is a good target for exercise, we will show people that maintaining a flat glucose curve is optimal for lifestyle and long-term metabolic health….We all know that eating a box of donuts is bad for us in a general, ill-defined sense, but without an immediate consequence like pain or death, it’s hard to feel compelled to overcome the powerful rewards of smell, texture, and taste.

By quantifying the consequence of a choice in real-time, we can effectively close the loop on diet, connecting a specific action to the nature and degree of the reaction, and allowing us to continuously improve our choices.

In another blog post, they elaborate the argument on better glucose control more:

Frequent glucose spikes have also been linked to inflammation, blood vessel damage, weight gain, and other changes that predict poor long-term health. And though absolute glucose levels matter, studies show that large spikes and dips in blood sugar can damage tissues more than high but stable numbers. Based on this research, we believe that glucose stability is critical to improving metabolic health.

An opinionated but abbreviated summary of the studies in that link is:

- On blood vessel damage: there is suggestive evidence that measuring spikes of blood sugar after meals in diabetics (“post-prandial” hyperglycemia) may better predict health consequences like heart disease versus average blood sugar, and that medications that blunt that spike may work better than other diabetes meds, but this seems far from settled. More importantly, extrapolating this to non-diabetics, who, by definition, cannot have post-prandial glucose spikes that exceed 199 mg/dL, is a stretch.

- On weight gain: The carbohydrate-insulin theory of obesity is far from obviously correct. At most, it is one of a few plausible theories to explain the obesity epidemic. Here is a good Twitter thread from someone arguing against it, but with proponents of both sides linking to relevant evidence that is worth reading.

- On glucose oscillation damaging tissues: this study shows that intentionally varying blood glucose levels into spikes and dips increased markers of blood vessel dysfunction and oxidative stress more than a continually high blood sugar. The connection to long-term health is uncertain.

A better summary of the literature is this Peter Attia blog post, which cites several studies:

higher glucose variability and higher (and more) peak glucose levels are each independently associated with accelerated onset of disease and death, even in nondiabetics_…_In the vast majority of cases, today’s normal individual is tomorrow’s diabetic patient if something isn’t done to detect and prevent this slide. Not only that, but prospective studies also demonstrate a continuous increase in the associated risk for cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular death, and deaths from all causes throughout a broad range of HbA1c values beginning at 5.0%. Similar trends are observed for elevated HbA1c values and higher rates of frailty, cognitive decline and dementia, COVID-19 hospitalizations and death, and cancer mortality, suggesting that lowering your average glucose levels even when they might be deemed normal by traditional cutoff points can make a difference.”

In addition, there are very high-quality mouse studies done by the NIA ITP showing two different drugs that lower postprandial glucose peaks (acarbose and canagliflozin) improve male mouse lifespan.

The overall finding from these epidemiological studies is that even within non-diabetic populations, a higher A1C tends to predict (years later) higher disease risk, and that higher glucose variability is an independent risk factor from higher average glucose. There aren’t any intervention studies in humans showing that lowering A1C outside of diabetics, or intervening on postprandial hyperglycemia, reduces risk. There are other explanations worth considering– for example, does poor overall health cause both more glucose variability and higher risk years later? – but I find this reasonably compelling.

However, there’s no data that CGMs will modify that risk. In fact, the data that wearables (of which CGMs are a subset) have positive health effects at all is pretty flimsy. This makes sense, in that we should be skeptical of small things impacting individual behavior in general. To their credit, Levels appears to be sponsoring a trial “Optimal Metabolic Health Through Continuous Glucose Monitoring” to try to answer this question, but clinicals.gov page doesn’t have an update since 2022 and a quick skim of the Principal Investigator’s pubmed page didn’t show any sign of publications based on this trial. The number of secondary outcomes also doesn’t inspire confidence, as unless all are reported in the follow-up papers, it allows for p-hacking.

The dream study would directly answer the following question: In non-diabetics, does being randomly assigned a Levels device affect important behavior or health outcomes? In order of practicality:

- Studying some health outcomes in a non-diseased population would take an impractically large and/or long trial, since measuring something like heart attack risk, which would be very low in a healthy population, would require waiting a long time or using a huge sample to acquire enough events.

- Some outcomes, like weight loss, would be more practical, and would still be valuable to show– knowing that being randomly assigned a CGM caused weight loss would be quite valuable!

- Merely knowing that being randomly assigned a CGM reduced postprandial glucose spikes by, say, 10%, in non-diabetics, would still be valuable, though it would ultimately leave certain important question– do postprandial glucose spikes per se even matter, does that degree of glucose lowering have an effect on things we care about? – unanswered.

Stephen’s dissent: I don’t believe in the strong form of the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis (e.g. I believe calories matter most for weight control), but I think this overstates the evidence against CGMs. In linking this study, you conflate activity trackers (FitBits and mobile health apps) with CGMs. I view this as questionable given that most metabolic health problems in the US are at least largely dietary and therefore I’d expect CGMs to have a much bigger impact on them than step trackers. That’s the primary piece of evidence against CGMs you cite, so besides this it mainly comes down to 1) how much you buy the various snippets of evidence you cited for the connection between glucose spikes and metabolic health and 2) priors.

On top of that, I suspect you and I just disagree on how much one should be willing to trade an imperfect proxy for faster feedback loops. As Max Hodak puts it, I view having “strong gradients” (aka directional fast feedback loops) as extremely important for progress and therefore view CGMs with a realtime UX to close the loop as a big step forward. I maybe wrongly place your view as closer to the medical one that places a lot of emphasis on not using the wrong metric. IMO, this view makes a lot of sense in the context of tests where subsequent interventions (e.g. surgery) can be extremely costly and dangerous but less in cases where behavioral change is cheap. Because of this, my summarized view is that as long as one doesn’t use them as their only metric it’s probably ok that CGMs are not a perfect biomarker for all-things-considered metabolic health and they’re still probably valuable for many people who want to understand how food affects them to try.

CGMs as metaphor #

Willy, Stephen, and Eryney’s shared view

The idea of a continuous glucose monitor suggests the idea of a CxM monitor– continuous (or highly frequent) monitors of many physiological variables. Here are some examples from clinical medicine:

- Arterial line to measure real-time and precise blood pressure

- Flow-trac to measure key cardiac variables in real-time

- Pulse oximeter to measure blood oxygen saturation

Stepping back, current wearables have various sensors that directly measure or infer various physiological parameters, and then generate scores to summarize that data. In the Oura ring case, it measures heart rate, heart rate variability, respiration, body temperature, and movement, and then generates a sleep score, readiness score, and activity score.

Without delving too deep into any specific wearable, wearables generally do a good job measuring what they purport to measure, but the connection to long-term health outcomes down the road is currently very tenuous. Most of the claims depend on behavioral change coming effectively for free along with more accurate measurement and self-knowledge, and I (Willy) am skeptical given the failure of calorie labeling to nudge the obesity needle.

More importantly, the much better case for wearables should instead rely on the following arguments:

- Wearables are fun

- Consumers appear to enjoy knowing more information about their health, even if it doesn’t help them– in fact, they’re willing to pay hundreds of $ for this! Consumer freedom is good!

- Wearables will probably help research

- “Big data works”: in the long-run, given the success of LLMs at getting smarter by hoovering up any and all text data, simply generating more data for future biology-oriented AI to train on seems like a sensible move. Other evidence along these lines is the success of the UK biobank and other similar efforts that link genotype, phenotype measurements, and EHR (electronic health record) data.

- Biological research especially lacks strong sources of high quality temporal data

- Wearables will probably get cheaper

- While other medical data won’t, because the latter is much more dependent on skiller labor (to draw blood, physically run blood samples, etc.), and therefore subject to Baumol’s cost disease. By contrast, wearables have become more sophisticated while staying at roughly the same price point overtime. I expect this trend to continue, though I haven’t studied this question in-depth.

- Wearables will probably get better:

- Getting beyond the traditional biomarkers captured in blood-based assays is a critical component of generating deeper data to feed into powerful ML models. While much consumer technology today is focused on capturing vitals like heart rate and blood oxygenation, the next wave of wearables ought to focus on things that point to our health on a molecular level.

- Hormones seem like a promising next step, and presents a substantial opportunity beyond insulin. The early stage company Eli Health is working on creating a consumer-targeted device for daily monitoring of various endocrine markers from saliva alone, with a specific goal of targeting reproductive health. A line can further be extended to integration into a wearable. Nothing quite as fun as licking a metal probe on your watch! Once the technology is there and a market is proven we’ll inevitably see movement into the men’s health space as well.

- We can’t get real time omics data on a cheap enough basis to make this feasible today, but the rapid progress of long read sequencing from companies like Oxford Nanopore will inevitably open up new possibilities with integration into wearables. While the timeline seems a little aggressive, researchers at IMEC are currently working on bringing this vision to reality.

- Wearables may allow for an end-run around siloed health data,

- though the latter will have much more sophisticated (and non-overlapping) data, at least for the medium-term.

- This matters more for the US healthcare and research system, which has been underwhelming in its equivalent to the UK Biobank (eg, the NIH AllofUS and the Million Veterans program have not produced nearly as many papers as the UK Biobank)

- Wearables might eventually be useful (to consumers, and not just researchers), if there’s data showing it actually changes behavior or outcomes we care about.

Put together, these are reasons to be hopeful that recreational wearables, while currently of questionable utility to consumers, will probably get cheaper and better, generate useful data for researchers to train ML models on, might eventually translate into surrogate markers for trials, and could route around a broken health privacy regulatory system. This pattern of recreational excitement leading to genuine innovation in an unrelated field can be best captured when considering the GPU’s highest utility, for a very very long time, was purely for gaming. Enough iteration and ingenuity eventually got us to where we are today with scientific computing and AI.

The best part about this is it highlights an underappreciated (but common) form of funding publically useful R&D: make early products attractive to rich people, and as costs drop, adoption will scale correspondingly. If such products generate positive externalities, all the better!

The future of CxM #

Stephen and Eryney’s view:

Right now, wearables are limited by the readouts they focus on, which is mostly dictated by what humans can currently make sense of. While a good start, glucose, heart rate, and even blood oxygen levels provide coarse-grained snapshots of overall biological state that work better for flagging problems than for identifying root causes. All of the above treats the future of CxM as an incremental progression expanding into similar readouts.

Instead, we can imagine a more radical future that, to be clear, assumes multiple engineering breakthroughs. To understand the full power of CxM, we should envision continuous monitoring that captures higher resolution biological variables such as transcriptomics, the full suite of hormones (cortisol, ghrelin, norepinephrine, testosterone, etc.), gut health, EEG, accelerometer, and potentially other important biological variables. At a certain point, a phase shift could happen where the scope of the measurements combined with the spatial and temporal resolution could make the data something closer to a comprehensive real time snapshot of biological state.

For individual health, this could allow us to track the impact of a whole range of interventions more closely. As an example, this might look like tracking liver enzymes minute-by-minute after starting on a new prescription (at different doses no less) or monitoring how different forms of exercise shift your transcriptomics. Paired with ML, a nice UX, and other means of parsing the data, this would be a realtime dashboard for what’s going on in a person’s body.

Having so much high resolution real time data could also improve research. Much of biological function emerges from dynamics, yet biological research often requires reconstructing temporal trajectories (see, for example, RNA velocity) using careful methods vs. observing them directly or relying on very coarse-grained snapshots at the level of days or even weeks rather than seconds, minutes, or hours. Measurements like transcriptomics currently require removing tissue and “freezing” it to get a snapshot of the molecular state at biospy. This means we rarely have concurrent readouts from multiple different types of measurements across scales (e.g. transcriptomics, hormones, heart rate, glucose, etc.) If research could instead start with data coming from high temporal resolution on a rich set of concurrent readouts, researchers could gain more information about how their target of study impacts biological systems.

As a clinical example, imagine if Phase I-III trial collected these measurements on subjects throughout the trial. Just as real time monitoring of engineered systems can help avoid catastrophic outcomes, monitoring all this information in trials could help notice and avert expected and unexpected adverse events. And similar to how airplane black boxes allow reconstructing the important information that led to a crash, in cases where adverse events still occur, having the full history of these metrics could enable better root cause analysis of failures.

Again, actually reaching this world requires many breakthroughs in our ability to noninvasively, nondestructively, and cheaply track so many markers and layers of biological state. However, achieving this goal would not just marginally improve health or research but would instead level up our ability to understand and manipulate human (and animal) biology.

Willy’s dissent:

I agree that a CxM would be very valuable in research for the reasons you mention, but I have serious reservations about its clinical utility. Apart from the hard technical problems that lie between current capabilities and this vision, the problem of “why does this real-time multi-dimensional data feed even matter” would need answering. The central problem, conditional on this impressive technical feat being achieved, is going from this to a clinically or individually actionable answer. One approach, consistent with the current regulatory and payer pathway for medical-grade CGMs, is running an RCT, looking at 1 or more clinical endpoints (1)Clinical endpoint is some outcome that we care about for its own sake: survival, self-reported quality of life score, avoidance of heart attacks or strokes, etc. This is contrast to a surrogate endpoint: a biomarker of no intrinsic interest, but which correlates with a clinical endpoint, and whose change is thought to predict a chance in a clinical endpoint: LDL cholesterol is one example. compared to standard-of-care, and approving (and insurance paying) on that basis. A looser alternative would be validating this health metric on a clinical endpoint– perhaps by conducting a trial as described before– and then letting that health metric be the basis of subsequent approvals (using the health metric as a “surrogate endpoint”). It’s hard to imagine either of these approaches eventually scaling to a future CxM tracking overall “health” or biological age or “readiness score” with some ML model getting input from two dozen different data sources. If we assume this CxM can bypass FDA oversight as a “recreational’’ wearable, we are still left wondering why we should trust that monitoring a “health” metric would improve our health. If my Oura ring or Eight Sleep mattress tells me I slept badly, but I feel fine, why should I trust it? If my workout tracker tells me my readiness score is low, but I hit a gym PR, who was right? Without external validation, these metrics quickly lose relevance.

I agree that in the limit, high enough resolution biological monitoring should enable high resolution understanding, but between the present and that futurist vision, I’m unsure how useful CxM’s will be. A milestone that would push me towards “this CxM might be useful, and not require a trial demonstrating clinical utility for me to buy in’’ is a CxM in a mouse that could reliably predict future aspects of a mouse’s health and anticipate the effects of interventions on it. Validating the importance of these real-time measurements in a mouse (whose lifespan is 2- 3 years) would be logistically feasible.

Final comments #

Wearables today may provide value to users by making them more attuned to their health via metrics like heart rate and sleep patterns, as well as providing immediate information on responses to behavioral change, but these benefits are uncertain. For researchers, current wearable tech might provide modest value in aggregate. Over the longer-term, better and novel sensors, adopted at scale, might provide much more value– all helped along by the industry of “recreational wearables” whose R&D is subsidized by wealthy and health-conscious users.